Table of contents

- Intro go CSP Concurrency model in Go (routines, channels, mutex, callback)

- CSP concurrency patterns

- Mutex

- Deadlocks

- Concurrency Patterns

Introduction

you can head over to this Repo, in which I’ve maintained all of the code examples below.

Go’s built-in support for concurrency is one of its most significant features, making it a popular choice for building high-performance and scalable systems. In this article, we’re going to explore the concepts of concurrency in Golang, including its core primitives, such as goroutines and channels, and how they enable developers to build concurrent programs with ease.

First things first, let’s begin with some concepts to ensure we’re all in the same context!

Concurrency vs Parallelism

Concurrency in Go is the ability for functions to run independently of each other.

You see, it’s that simple 😀, but we can talk a lot more about that simple fact just enough to see it’s not that simple 😂

As Rob pike once said:

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once

That’s the key difference between concurrency and parallelism, if you’ve got a good mental model of each one’s characteristics, it will be an easy mission to tell the difference!

Before talking about the difference in depth, you should have a clear understanding of processes and threads.

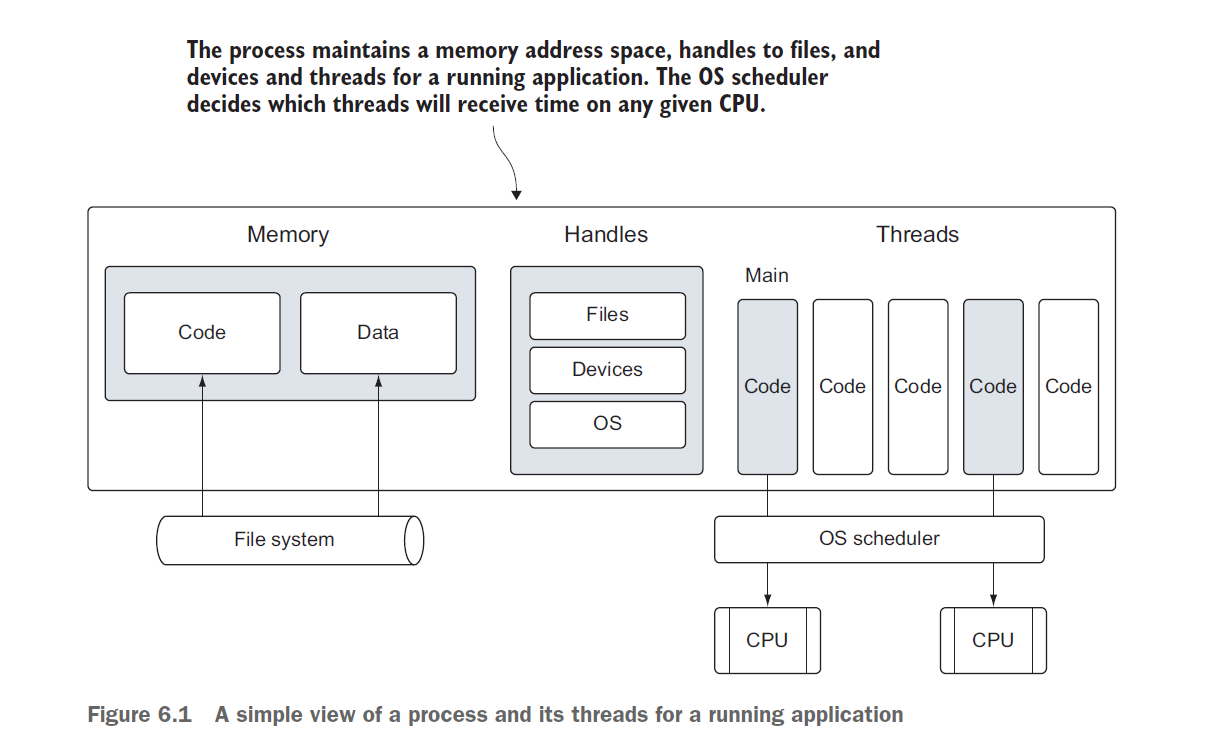

You can think of a process like a container that holds all the resources an application uses and maintains as it runs.

A thread is a path of execution that’s scheduled by the operating system to run the code that you write in your functions.

The operating system schedules threads to run against processors regardless of the process they belong to.

The operating system schedules threads to run against physical processors and the Go runtime schedules goroutines to run against logical processors. Each logical processor is individually bound to a single operating system thread

These logical processors are used to execute all the goroutines that are created. Even with a single logical processor, hundreds of thousands of goroutines can be scheduled to run concurrently with amazing efficiency and performance.

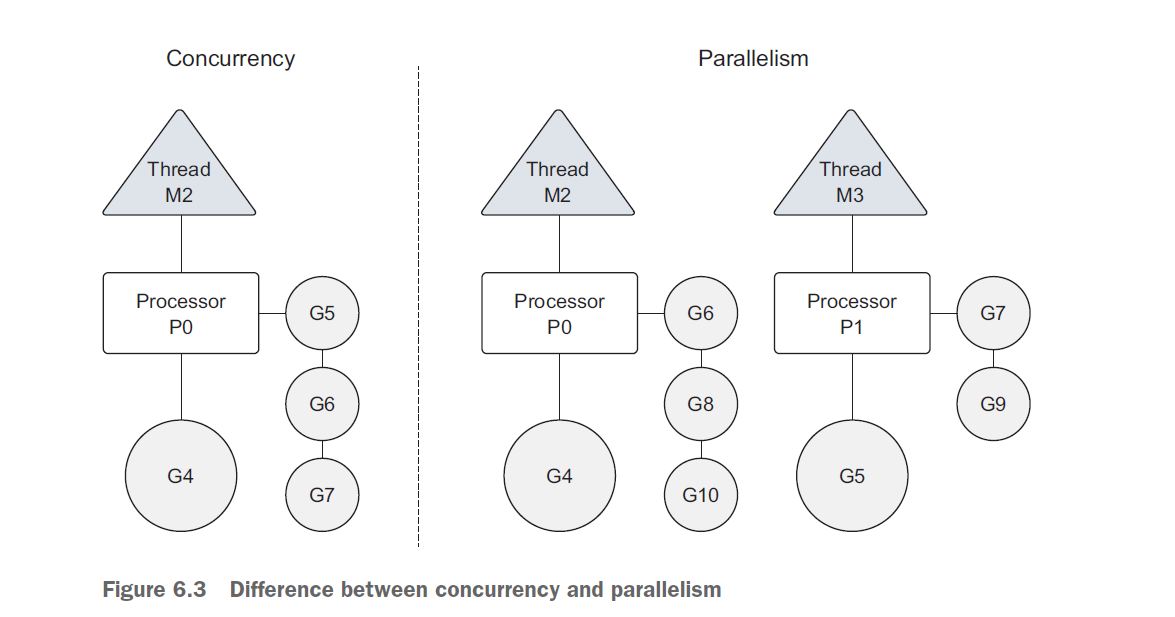

Concurrency is not parallelism. Parallelism can only be achieved when multiple pieces of code are executing simultaneously against different physical processors

Parallelism is about doing a lot of things at once. Concurrency is about managing a lot of things at once

Concurrency is when different (unrelated/related) tasks can be executed on the same resource (CPU, machine, cluster) with overlapping time frames, While Parallelism is when related tasks or a task with multiple sub-tasks are executed in parallel (same start - probably same finish - time)

In many cases, concurrency can outperform parallelism, because the strain on the operating system and hardware is much less, which allows the system to do more. This less-is-more philosophy is a mantra of the language.

If you want to run goroutines in parallel, you must use more than one logical processor.

When there are multiple logical processors, the scheduler will evenly distribute goroutines between the logical processors

But to have true parallelism, you still need to run your program on a machine with multiple physical processors

If not, then the goroutines will be running concurrently against a single physical processor, even though the Go runtime is using multiple threads.

Go’s Concurrency allows us to:

- Construct

Streaming data pipelines - Make efficient use of I/O and multiple CPUs

- Allows complex systems with multiple components

Routinescan start, run and complete simultaneously- Raises the efficiency of the applications

Goroutines

When a function is created as a goroutine, it’s treated as an independent unit of work that gets scheduled and then executed on an available logical processor.

Goroutines are extremely lightweight and efficient, with minimal overhead, which means that you can create thousands of them without any significant impact on the performance of your program.

A goroutine is a simple function prefixed with go keyword

| |

The term goroutine comes originally from coroutines

A coroutine is a unit of a program that can be paused and resumed multiple times in the same program, keeping the state of the coroutine between invocations, generator functions in python is an implementation of coroutines

While a subroutine is a unit of a program that’s executed sequentially, invocations are independent so the internal state of a subroutine is not shared between invocations, a subroutine finishes when all instructions are executed, cannot be resumed afterward

Go’s runtime scheduler in depth

Having a good understanding of Go’s runtime scheduler gives you a clear and consider understanding of how concurrency gets handled in Golang, so let’s uncover some of the runtime behavior

The Go runtime scheduler is a sophisticated piece of software that manages all the goroutines that are created and need processor time. The scheduler sits on

top of the operating system, binding the operating system’s threads to logical processors which, in turn, execute goroutines. The scheduler controls everything related to which goroutines are running on which logical processors at any given time.

Execution steps of goroutines

- As goroutines are created and ready to run, they’re placed in the scheduler’s global run queue.

- Soon after, they’re assigned to a logical processor and placed into a local run queue for that logical processor.

- From there, a goroutine waits its turn to be given the logical processor for execution.

Sometimes a running goroutine may need to perform a blocking syscall, such as opening a file.

When this happens, the thread and goroutine are detached from the logical processor and the thread continues to block waiting for the syscall to return. In the meantime, there’s a logical processor without a thread. So the scheduler creates a new thread and attaches it to the logical processor.

Then the scheduler will choose another goroutine from the local run queue for execution. Once the syscall returns, the goroutine is placed back into a local run queue, and the thread is put aside for future use.

🟢 If a goroutine needs to make a network call, the process is a bit different. In I/O this case, the goroutine is detached from the logical processor and moved to the run time integrated network poller

🟢 Once the poller indicates a read or write operation is ready, the goroutine is assigned back to a logical processor to handle the operation. There’s no restriction built into the scheduler for the number of logical processors that can be created. But the runtime limits each program to a maximum of 10,000 threads by default

Now let the fun begin,

In this section, we are going to play around with the number of logical processors assigned to handle each situation below and see how this affects the overall behavior.

| |

If you tried to run the code above, you will see the following output:

| |

A waitGroup is a counting semaphore that can be used to maintain a record of running goroutines

For each time wg.Done is invoked, the counter is decreased by 1 till it reaches 0 and then the main can terminate safely.

The keyword defer is used to schedule other functions from inside the executing defer function to be called when the function returns, based on the internal algorithms of the scheduler, a running goroutine can be stopped and rescheduled to run again before it finishes its work

The scheduler does this to prevent any single goroutine from holding the logical processor hostage. It will stop the currently running goroutine and give another runnable goroutine a chance to run

Here’s a diagram of what’s already happened

🤔 What if we tried to change the number of logical processors from 1 to 2, what do you think goin’ to happen❓

| |

probably you will see output looks like this

| |

It’s important to note that using more than one logical processor doesn’t necessarily mean better performance, Benchmarking is required to understand how your program performs when changing any configuration parameters runtime

Another good example to demonstrate the idea of using a single logical processor more clearly is by doing some heavy work

| |

notice this output

| |

Goroutine B begins to display prime numbers first. Once goroutine B prints prime number 4591, the scheduler swaps out the goroutine for goroutine A. Goroutine A is then given some time on the thread and swapped out for the B goroutine once again. The B goroutine is allowed to finish all its work. Once goroutine B returns, you see that goroutine A is given back the thread to finish its work.

Remember that goroutines can only run in parallel if there’s more than one logical processor and there’s a physical processor available to run each goroutine simultaneously.

CSP

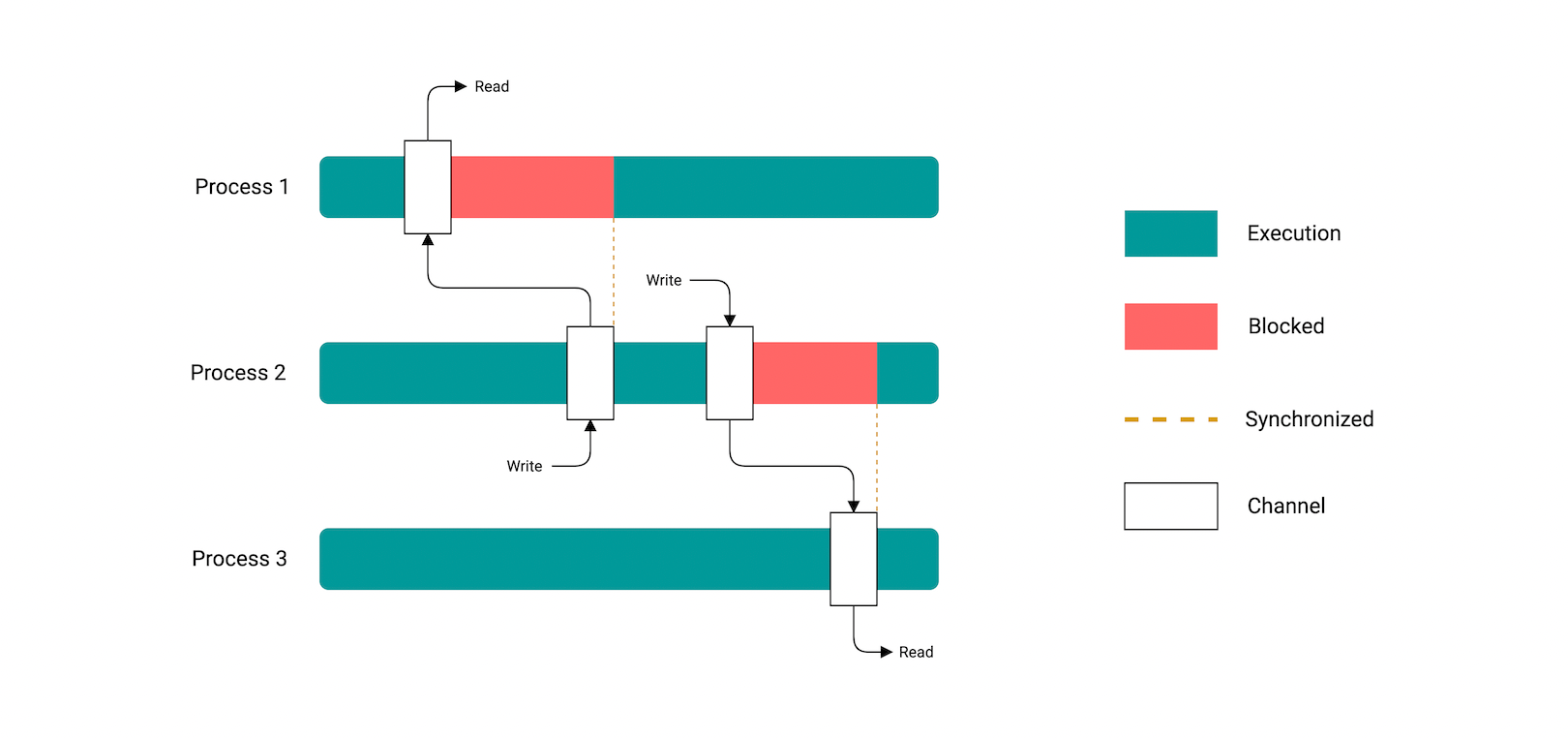

Concurrency synchronization comes from a paradigm called communicating sequential processes or CSP. CSP is a message-passing model that works by communicating data between goroutines instead of locking data to synchronize access. The key data type for synchronizing and passing messages between goroutines is called a channel

CSP provides a model for thinking about concurrency that makes it less hard

Simply take the program apart and make the pieces talk to each other

Head over to this presentation by the creator of Erlang which discusses this concept in an in-depth details

Basic Concepts

- Data race: two processes or more trying to access the same resources concurrently maybe one was reading while the other was writing

- Race conditions: the timing or order of events affects the correctness of a piece of code

- Deadlock: all processes are blocked while waiting for each other and the program cannot proceed further

- Livelocks: processes that perform concurrent operations, but do nothing to move the state of the program forward

- Starvation: when a process is deprived of necessary resources and unable to complete its functions, might happen because of

deadlockorinsufficient scheduling algorithms

Deadlocks

There are four 4 conditions, known as Coffman conditions which when are satisfied, then a deadlock occurs

mutual execution

Hold and wait

No Preemption

Circular wait

Mutual Execution A concurrent process holds at least one resource at any one time making it non-sharable.

- Hold and wait A concurrent process holds a resource and is waiting for an additional resource.

Process 2 is allocating (holding) resources 2 and 3 and waiting for resource 1 which is locked by process 1.

- No preemption A resource held by a concurrent process cannot be taken away by the system. It can be freed by the process of holding it.

In the diagram below, Process 2 cannot preempt Resource 1 from Process 1. It will only be released when Process 1 relinquishes it voluntarily after its execution is complete.

- Circular wait A process is waiting for the resource held by the second process, which is waiting for the resource held by the third process, and so on, till the last process is waiting for a resource held by the first process. Hence, forming a circular chain. (All if waiting)

Conclusion

Go’s runtime scheduler is very intelligent at handling concurrency, with algorithms designed to take care of the workload of your software and distribute it among available threads is something very efficient for your system resources and overall performance!

In the next write-up, we’ll continue our journey talking about conventional synchronization such as mutexes, channels, and Data races in further detail, stay tuned!

Lastly, thanks for reading this write-up, if it helped you learn something new, please consider buying me a cup of coffee ♥.